…soils not only speak to us, but can be great subjects for art and music…soils truly are sexy. – Dr David Eldridge

I’ve been puposely listening to the sound of soils for the past three years. It’s been a process of digging into the layers, questioning everything, reading extensively, and creating an attentive listening discipline that demands time, stillness, and an open mind.

Compared to the clear, resonant melody of solo birdsong or a choral dawn chorus, the scritchy scratches, crunchy crackles, gurgles and soft thumps of life beneath our feet are a test to the human ability to tune into life that more often goes unseen, unheard, and unnoticed. It can at first sound like white noise.

In its simplest form, soil is made up of mineral particles, organic matter, water, air and living organisms that slowly and continuously interact with each other. Weathered rock reduced to tiny particles that are moved and manipulated by plants, bacteria, fungi, invertebrates, animals and humans through cycles of growth, decay, and at times, disruption—generating enormous amounts of energy in the process. Sound is part of this energy mix.

A 2023 study[1]claims soil is home to 59 percent of all life on Earth; the most biodiverse singular habitat on the planet. The activity and processes of some of those species create vibrations that can be picked up by sensitive microphones.

Identifying acousmatic sounds

Sub-surface sounds are central to much of the fieldwork I do. Many of the sounds I listen to and record are acousmatic sounds. These are sounds where the source is hidden or unknown. Unlike the recording of birdsong where you often see the bird species, or a range of sounds for that species have already been clearly identified, it’s hard to know whether the rustling or scratching sound in soil is coming from a worm or burrowing larvae, unless it’s something known to have a signature sound like burrowing field crickets or mole crickets. To identify acousmatic soil species, you have to dig up the recording site. It’s only after working in and attentively listening to the soils in my garden, I now know the sound of beetle larvae.

Work is being done to try and identify the species behind acousmatic sounds in soils. It’s the next step in fully adopting the use of ecoacoustics to monitor soil health[2][3], underpinned by the idea that noisy soils are healthy soils. From a creative perspective, it isn’t always necessary to know what the source of the sound is, but it can certainly help with the backstory, or when talking about creative ecoacoustics with scientists, researchers, field professionals, and farmers.

On-farm listening lab

I had that very opportunity this month when I was invited to set up a listening lab on the farm where I’ve been conducting my SOIL+AiR creative future landscapes project. A busload of international delegates on their way from Sydney to Adelaide for the International Rangeland Congress (2-6 June) stopped into ‘Willydah’, the Maynard family farm between Narromine and Trangie, to learn more about innovative, agro-ecological farming practices, soil ecoacoustics, and to listen to the soils on the farm.

Led by Dr David Eldridge from the University of NSW and other Australian rangeland ecology specialists, 20 international visitors spent three hours on ‘Willydah’, fascinated by the sound of damp, wintery soils in a paddock of saltbush and mixed grasses. They also leaned into Bruce Maynard’s presentation of his cropping and animal management philosophies and practices[4].

The listening lab consisted of four microphones set up on an old Zoom F6 with a portable speaker instead of headphones. I had one contact microphone attached to the base of grass at ground level, another contact mic buried about 10cm deep in soil, a geophone with the 5cm probe pressed into the ground, and a hydrophone also buried about 10cm deep—hydrophones are useful in wet soil, something I don’t work with very often. Listeners were invited to put their hands on the pulsing ends of the speaker to feel the vibrations in the soil as well as hear them. This is not how I would record soils. This microphone array and playback set-up was to allow a large group of listeners to access the experience, catering for differing levels of interest, hearing ability, and the time constraints. Despite low soil temperatures following rain and a cold change, and the icy, southerly wind gusting on the day, it worked reasonably well.

To successfully record soils for creative purposes I need the following—as little human movement within the recording environment as possible; a 32-bit float audio recorder with low self-noise; fewer microphones; sunshine, no wind, and warm, moist but not wet soils. I rarely have perfect conditions, so I’ve learned to adapt my field practice to the day, making adjustments as needed.

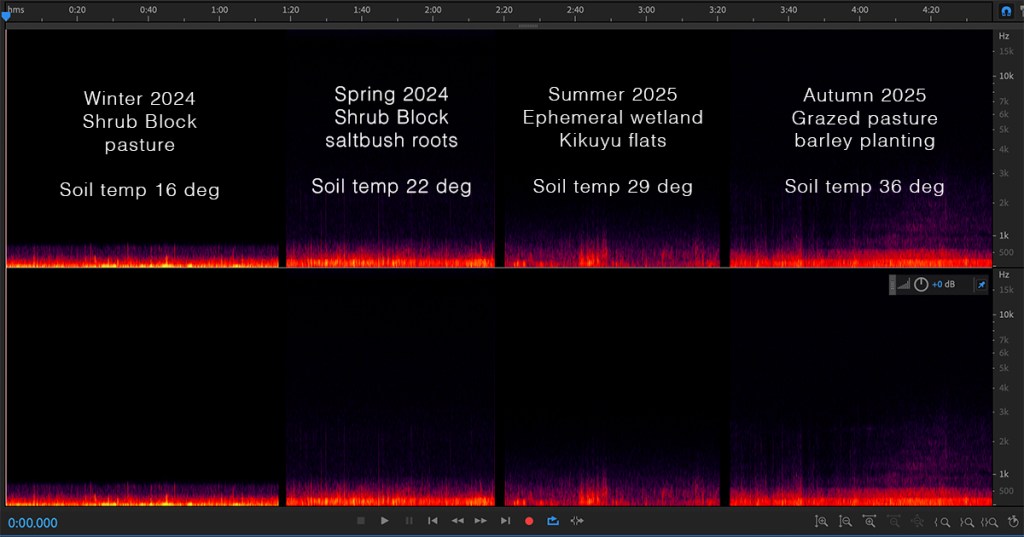

There were some great questions during the listening lab about what could be heard through the speaker; the impact of human activity on the site; how much moisture and soil temperature influence the sounds you might hear; concerns about the absence of insect noise in the recordings I’ve been making in recent years; developments in the field of soil ecoacoustics and how datasets shape soil acoustics quality indices, and; what spectrograms bring to the analysis of soil recordings. We spent some time looking at and listening to the spectrograms of seasonal soil recordings I’ve captured on ‘Willydah’ since July 2024.

Stop. Be still. Listen.

Two further questions put to me were about what institution I belonged to and what my field of research is. I explained at the start that having an artist in residence on a farm is not common in Australia, but despite my decades-long background in agriculture, natural resource management, and the arts, I am not attached to any institution. I am not a science researcher, and unfortunately, the vast majority of my field-based work is self-funded.

So, why would an artist do this?

How I answer this question depends on who is asking. My response to an academic or applied science audience is my creative work in soundscape composition, sound installation, and writing is a form of extension work or science communication. Through art, I reach audiences traditional science communication or extension programs will never engage. Informed by science, I see my work as a provocation, a conversation starter about the wonders of nature’s persistence and struggle in a human-shaped world. How do we encourage people to care about a world they do not know or cannot experience? Art has the ability to provide some of the answers to that question.

In answering the question for a creative audience, who often ask whether I work in protected natural environments—because a lot of ecological artists do, my answer is that when you consider agriculture accounts for over half of Australia’s land use[5], there’s a lot of creative scope in exploring the state of these altered environments, their management, and their future. The space between what is and what could be raises so many questions and is incredibly fertile ground.

Agricultural land management is also where the greatest change needs to happen. Protected environments are wonderful places to explore and important ecosystems to conserve and celebrate, but for me, there are far greater possibilities and gains to be had within the privately-owned farming landscapes of Australia. These are not just places to pass through on the way to an eco-tourism or eco-cultural experience, these are places to stop. Be still. To listen and learn. It’s where human and more-than-human worlds intersect on a daily basis.

Bruce Maynard is oft known to say: Not everyone can be a farmer, but everyone can know a farmer. The SOIL+AiR project has provided not only the opportunity for me to share the Maynard’s farm in an intimate and immersive way with audiences who will never step foot on the place, it has provided Bruce and his family with a chance to experience a place they know intimately from a new perspective—through the sounds and images I’ve brought to the surface in my time on the farm.

Magic and mischief in unexpected places

As David Eldridge wrote on LinkedIn about listening to soils on the visit to ‘Willydah’, …soils not only speak to us, but can be great subjects for art and music…soils truly are sexy.[6]

The last thing I shared with everyone before they got back on the bus is every farm has an in-house orchestra. The resonance of fencing wire played by the wind is an incredibly melodic and moving listening experience, something I will play with in developing soundscape compositions over the coming year*. From an ecoacoustics perspective, the constant nature of these sounds in landscapes carved up with wire fencing, often unheard by humans, is potentially the equivalent of tinnitus for other species whose hearing range is greater than ours. It’s another perspective to consider, and another story to tell through the making of art with sound.

[1] https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2304663120

[2] https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.14738

[3] https://soilacoustics.com/

[4] https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/stories/b-maynard

[5] https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/products/insights/snapshot-of-australian-agriculture

[6] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7333086799243747329/

* A recently awarded Create NSW Creative Steps: New Work grant is funding the creation of digital artworks for exhibition, community engagement activities, and a project publication documenting the SOIL+AiR project.